Europe

Declining Russian Influence: Russia’s Attitude Towards New and Future NATO Members

Czech Republic

Moscow generally refrained from exploiting ethnic problems in the Czech Republic. However, the position of the Roma minority was sometimes brought to attention by Russian officials and media to represent the Czech Republic as not democratic enough. Moscow has also expressed concern over alleged unfair treatment of ethnic Russians enforced by the Czech authorities.

According to Slovak government reports, Russian information agencies have hired members of the Slovak secret police in order to sabotage the expansion of NATO to the Czech Republic by organizing plots meant to exploit rivalries and to fuel doubts on the ability of the Czech Republic join NATO. According to the Czech counterintelligence service, international organized crime that acts in the country has mostly links with Russia. Czech intelligence noted a growing interest of Russian intelligence services for information on modern military equipment that NATO brings in the Czech Republic. Czech analysts have complained about the refusal of successive governments to reform the four information services of the country, indicating that some senior officials continue to cooperate with Moscow.

Hungary

Moscow’s position became even harsher after Hungary has requested NATO membership. Russian propaganda attacks on Hungary were more moderate than those against Poland because the country does not occupy a strategically difficult position, as it is not so close to the CIS region. Moscow has not released any specific threat against Hungary as the country joined NATO. The comments of prime minister, Viktor Orban, in October 1999, regarding the possibility of allowing U.S. to place nuclear weapons in Hungary “in times of crisis” have outraged Russian officials and led to postponement of Prime Minister Kasyanov’s visit to Budapest.

Since the election of Putin, Moscow has tried to boost the sale of arms to former signatories of the Warsaw Pact and to regain some of the lost market due to Western intervention. However, Budapest has remained cautious about military dependence on Russia.

Russian companies have been trying to invest more and more in the Hungarian energy sector through privatization. Russian capital has increased its role in Hungary in the last decade. The Hungarian authorities have noted this tendency with some fear and are believed to be imposing restrictions.

Moscow has tried to discredit the Hungarian pro-Western and pro-NATO government, focusing on Roma issues, which they consider a more sensitive issue in Western capitals.

Poland

Russian propaganda strongly attacked Poland’s efforts to establish regional groupings with its post-soviet neighbors and the ones from Central Europe. Moscow feared that structures such as the Visegrad group would exclude Russia and attract CIS countries in the Western orbit. Moscow believes that Poland is its main regional competitors in exercising influence over the CIS countries.

Relations with Russia became even more strained after Poland’s accession to NATO in 1999. Kremlin was trying to demonstrate that the new members of NATO will adopt an attitude of opponents of Russia. Officials were complaining about NATO’s increased activity at the borders of Russia, including military flights over the Kaliningrad region of Russia.

Although Warsaw has focused much of its foreign trade to the West, it remains heavily dependent on Russia for energy supplies. Moscow thus uses its “energy diplomacy” to achieve political gains.

In a movement to ensure energy diversity and decrease dependence on Russia, in September 2001, Poland signed an agreement with Norway, although Norwegian gas suppliers prices were 30% higher than Russia.

Due to Poland’s ethnic homogeneity and the absence of any significant autonomist movements involving Russian-speaking population, there weren’t too many opportunities for Moscow to exploit the ethnic issue to its advantage.

Russian services have had too few opportunities to provoke ethnic, social, religious or regional unrest in Poland or to incite anti-government feelings. As one of the most homogeneous countries in Eastern Europe, with a reasonable attitude towards minority rights and a small number of ethnic Russians, Poland has escaped some of the complaints raised by Russia to the neighboring Baltic states. Therefore, there was little chance of manipulation by the Russians on these issues.

Moscow has tried hard to discredit the Polish authorities to disqualify the country’s entry into NATO. Russian officials also tried to show that Poland was not a serious partner for Western institutions telling the Polish secret services and other secret services in Central Europe continued to spy on Alliance.

Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania

Russian leaders did not believe that they can realistically integrate the three countries in the CIS or other supra-structure. They tried instead to place Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania in a “neutral zone”, undefined, between NATO and the CIS and between Central Europe and Russia, in this way, Western influences could be minimized. Russian officials have lanched many warnings in the 90s on the fact that admission of the Baltic countries in NATO would lead to interruption of relations between Moscow and NATO and would lead to a new era of conflict.

Moscow was vehemently opposed to Balkan states’s entry in NATO and warned that such a move would bring to power the hard-line politicians in Russia, and this would hasten the appearance of a conflict with the Alliance. Kremlin argued that the admission of the Baltic states would create a strong barrier against Russia and claimed to have a decisive word in the Baltic republics security policies.

Kremlin tried instead to isolate the three countries internationally, generating tensions within and between the Baltic states and other states to block their acceptance into NATO, specially since the good relations with neighbors were an important condition to become a member of the Alliance.Moscow was manipulating the minority issue to demonstrate that all three governments are unable to achieve European standards of minority protection and human rights.

Russian authorities threatened the Baltic States, supported the economic conflict and claimed that these states represented a springboard for a possible NATO attack against Russia. Some politicians asked to take military measures to force the three republics to comply, and Foreign Minister Primakov called for a revision of certain post-Soviet borders. When direct threats did not have the desired effect, Kremlin resorted to incentives.

At the Easter European leaders’ high level meeting in Vilnius in September 1997, Prime Minister Chernomyrdin proposed several confidence building measures, under the name of “the Baltic Programme”. This included proposals for unilateral security guarantees offered by Russia if Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania remained outside NATO and bilateral guarantees offered by Russia and NATO.

Moscow continued to work towards the disqualification of the Baltic states as viable candidate for the Alliance. They invented internal and external problems such as NATO leaders to consider that the accession of the Baltic states would be too risky, creating new problems to the organization.

Moscow was disrupting Baltic economies to gain political advantage. Each government has tried to steer the economy to the West and to limit dependence on Russia and its susceptibility to blackmail. Moscow has tried particularly to control power transmission means, this being profitable both financially and politically. There were also attempts to discredit the intelligence and security in the Baltic countries to disqualify them for joining NATO.

Moscow has tried to create differences between Baltic leaders claiming that the Estonian and Latvian businessmen are skeptical about the integration into NATO and would prefer to expand trade and political ties with Russia.

When Putin understood that NATO expansion can not be stopped, he changed his strategy, believing that acceptance of NATO membership for the Baltic States combined with a stronger expression of the views of Moscow in NATO deliberations, could weaken the Alliance and undermine the relevance of extending. Baltic officials that it’s important that all three Baltic countries should be included into NATO simultaneously. This was the only way that future conflicts with Moscow could be prevented regarding the NATO membership, the possibility of rivalry could be reduced and could provide a safe environment for economic development. Any delay in joining of any Baltic state would have allowed Russia to develop its international influence by obtaining a firmer control in strategic sectors of local economies.

Russia has had some disappointments in the policy of the Baltic countries. It failed to attract the three independent states into its own orbit of security and proved unable to prevent their political orientation to the West and establishing close relations with the United States.

Slovenia

With the outbreak of Yugoslav wars in the summer of 1991, Russian policy has oscillated between supporting the integrity of Yugoslavia and the cold relations with Milosevic, who had supported the coup attempt in Moscow in August 1991. The central goal of Russian diplomacy was the preservation of Yugoslavia and maintaining domination over Serbia, according to the Soviet Foreign Ministry before the Soviet collapse (position inherited by his successor Russian), an independent Yugoslavia representing “an important element of stability in the Balkans and throughout Europe”.

In turn, Belgrade considered Russia as a useful ally because of Moscow’s veto in the UN Security Council during Belgrade’s attempts to create Greater Serbia. Yeltsin recognized the independence of Slovenia in February 1992 after it became clear that socialist Yugoslavia died.

Yet, in the early stages of the Bosnian war in 1992, Moscow strongly supporter Serbia, which coincided with the affirmation of a more aggressive foreign policy line. During the visit Foreign Minister Ivanov in Ljubljana, several agreements have been finalized and was stressed that the economic cooperation was steadily improving. Slovenian businessmen have made their presence felt in Russia more than ever, as the volume of investments increased. Slovenia and Russia plan to expand trade from the current $ 600 million annually, to at least one billion dollars by 2006. Discussions were held also around Russia’s debt to ex-Yugoslav countries. Slovenia should receive 207 million dollars of the total of 1.29 billion that Russia owes the successor states of Yugoslavia.

In Slovenia, Russia had few opportunities to exploit ethnic differences, as the country is predominantly homogeneous and there are no territorial claims from neighbors. Moscow had few opportunities to influence political processes in Slovenia. Moreover, most parties in Slovenia were prominent anti-Yugoslav and pro independence – positions that were contrary to Kremlin policy. It is believed that Moscow was clearly defending Yugoslav and Serbian causes. Still, Moscow is counting on the fact that it could enter in Zagreb on long term by economic cooperation and investment.

Slovakia

Slovakia from Merciar’s time became the only Central European state to accept the “Kvitinski doctrine” and signed a fundamental treaty with Russia. The doctrine was named after the Soviet deputy foreign minister, Yulia Kviţinski, who led negotiations in 1991 for bilateral treaties with all countries of the former Warsaw Pact, incorporating security clauses that deny them the right to establish “hostile alliances.”

Exclusion of Slovakia from the first round of NATO expansion was considered a diplomatic success of Moscow. As a result of NATO’s expansion, Moscow launched a warning on creating a multi-state alliance in the region, which could exclude Russia from any of its traditional “spheres of influence”. With the election of a democratic government in Bratislava in September 1998, Moscow’s influence began to be closely investigated. Putin administration also had to accept the invitation to join NATO addressed to Slovakia in November 2002 at the Prague summit.

Moscow did not need too many propaganda attacks and disinformation campaigns against Meciar regime, which was perceived as a valuable outpost of Russian interests in the middle of a Western-oriented region. Criticism against the democratic coalition who was ruling the country after the elections in September 1998 had become a common ground and Russian secret services bribed or blackmailed editors and journalists to send materials to the benefit of Moscow. There were suspicions in Bratislava that some negative reports on government security agencies were created and spread by Russian intelligence. Among them were allegations of lack of credibility of the Slovak security services and illegal sales of arms to regimes internationally sanctioned.

NATO leaders had expressed concerns over Slovak Intelligence Service (SIS) being involved in arms trafficking, working with Russian intelligence services, tapping journalist’s phones illegally and engaged in campaigns of denigration of some politicians, which could affect the national security of the country and the Alliance in general. NATO Secretary General Lord Robertson said that Bratislava has to convince the Alliance that their security bodies are to be trusted with the custody of classified information and that they have a credible and independent oversight of security.

The Slovak authorities have harshly criticized the reports according to which the SIS situation was raising serious doubts about the country’s ability to integrate into NATO and the EU. There were suspicions that the reports were exaggerated and falsified by activists associated with Meciar, which kept active links with Russian intelligence services, in a deliberate campaign of denigration of the government.

Bulgaria

Russia believes that the Black Sea states, Bulgaria and Romania, have strategic importance for several reasons. First, their control can help increase Russian influence in southeastern Europe, while the Black Sea itself is considered a zone of Russian domination, secondly, they form a bond of energy and infrastructure between Europe and Caucasian and Caspian regions. Thirdly, Bulgaria is seen as a historical ally that can help restore Russia’s advantage. Traditionally, Russia has sought to keep open the Bosporus straits between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean for its navy and raw materials. This was done in the late nineteenth century at the expense of all countries in the region, including Bulgaria and Serbia, who have become Russian quasi-protectorates. Today, Russia’s strategic ambitions are focused primarily on the impending flow of Russian energy supplies to the West, but not necessarily through the Bosphorus. Moscow intends to provide alternative routes through the Balkans, as a shield against potential bottlenecks in Turkey.

Much of the 90s, Bulgarian Socialists remained closely tied to Russia in December 1994, when they returned to power, Russia’s influence grew and it considered Sofia as an opponent of NATO’s expansion. During a visit to Sofia in March 1996, Yeltsin said that Bulgaria is the only Eastern European country to become a member of the Russian community. In March 1996, Duma’s President, Gennady Selezniov said that Russia and Bulgaria share a common strategic objective and supported Bulgaria’s neutrality, In contrast, the Union of Democratic Forces (UDF) who was in opposition was perceived as a dangerous element, which could lead the country closer to NATO. UDF’s election victory in April 1997 was seen by the Kremlin as a major obstacle, as the new Bulgarian government fully embraced the possibility of entering NATO. Moscow tried to divide the Union, seeking to corrupt officials and lawmakers with business proposals. It invested large sums of money to undermine the government, between 1997 and 2001. Resources were allocated to the media and several political parties to discredit the UDF and to promote the Socialists, who were more reliable. Pro-Russian lobby of the Bulgarian Socialist Party campaigned on behalf of Russian economic interests against Bulgaria’s accession to NATO.

Russia was determined to use Bulgaria as a strategic outpost to penetrate the region, based on cultural and historical ties with Russia and the country’s geostrategic position. Disintegration of the Soviet bloc questioned the manner in which Sophia could to protect the independence and promote economic development while maintaining balanced relations with Moscow. Russia continued to show a superiority complex towards small Slavic states and expected that Bulgaria would remain part of post-sovietic political, economical and security space. Its expectations were deceived in April 1997, when Bulgaria elected a reformist pro-NATO government and its progress towards entry into NATO generated tensions with Moscow.

When Russia realized that – in terms of not allowing Bulgaria to NATO, the stakes were lost, there was a new facet of the “Slavic-Orthodox” construct, some Russian commentators claiming that the Bulgarians, in fact, were not entirely Slav. The intention was to maintain the illusion that NATO propaganda is essentially a Catholic-Protestant organization, aiming against the East Slavic world.

Moscow consistently opposed the accession of Bulgaria to NATO, but failed to deflect Sofia’s application for membership, however, the Russian secret services engaged in a campaign to discredit the Bulgarian government by launching rumors which have circulated widely in Bulgaria, that the new prime minister, Simeon Saxe Coburg Gotha, was a puppet for the Russian mafia. Also, Moscow claimed that the United States forced Bulgaria to join NATO and pressured Sofia to weaken its relations with Russia.

There was no direct military threat from Russia against Bulgaria, but Moscow has regularly expressed dissatisfaction towards Bulgaria’s moves closer to NATO and Washington.

At the end of NATO war in Kosovo, Bulgaria refused to grant overflight rights to Russia in order to position troops in the province, until agreement was reached between NATO and Russia for a unified command of the peacekeeping forces. Yeltsin’s deputy, Andranik Migranian, described this decision as a hostile act of Sofia that “will enhance anti-Bulgarian feelings in Russia” and which may affect economic relations”.

Bulgaria’s decision to join NATO sparked Moscow’s officials protests. In August 2000, Foreign Minister accused Bulgaria of establishing excessively close relationships with NATO, warning that it is detrimental to the country’s traditional ties with Russia. A smoldering conflict between Moscow and Sofia is on planning the opening of U.S. bases and military bases in Bulgaria. Setting up of bases was welcomed by the Bulgarian authorities who saw it as a means to strengthen ties with Washington and bringing economic benefits to the country. Kremlin signaled Sofia about its strong opposition towards this initiative and asked to participate in negotiations on the projected bases.

The ethnic issue occupied a marginal place in Russian policy towards Bulgaria. Otherwise would have been shocking that in the name of “Slavic solidarity”, Moscow to instigate a conflict or to accuse Sofia of discrimination against its Muslim communities (Turkish, Roma, pomaka), which forms most of the country’s minorities.

Some Bulgarian companies have been involved in scandals involving the export of arms to dubious regimes, including equipment that could already be used by governments in the Middle East. Such a scandal involving spare parts for armored personnel carriers for Syria, was presented in the press on the eve of NATO Summit in Prague in November 2002.

Romania

Romania initially accepted the “Kviţinski doctrine” proposed by Moscow on the eve of the Soviet collapse. At the negotiations on the bilateral treaty, a clause was inserted by which both parties were denied entry into any military alliance perceived as hostile by any of the signatories. Following the disintegration of the Soviet Union, the treaty remained in Bucharest unratified and, to the disappointment of Kremlin, Romania started to adopt a more open pro-NATO position. Although there was no direct military threat against the country, it was clear that Russia was strongly opposed to foreign and security policies of Bucharest.

The persistence of the political crisis in the neighboring country of Moldova, was manipulated by Moscow to put in a negative light Romania’s foreign policy. The maneuver became clear in February 2002, as the conflict between the government and protesters was getting stronger in Chisinau. There were demonstrations organized by the opposition movement against the forced introduction of Russian as official language by the Moldovan Communist administration. However, Russian officials have presented demonstrations as a Romanian provocationt, aimed at the annexation of Moldova.

Romanian authorities have accused Moscow of maintaining the crisis in a fragile state, in order to break the pro-Romanian block, to have a more subordinate Moldova and in order to discredit the government in Bucharest, in the manner well known Russian officials have launched libel to the foreign policy of Romania and questioned Bucharest ‘s credibility as a potential ally of NATO. Communist authorities in Chisinau, with close links to Moscow, in turn inflamed speculation that Bucharest would promote a “revenge” against the Republic of Moldova if they were admitted to NATO.

In September 2003, after Romania received the green light for NATO membership, conflict broke out on the need for parliamentary oversight of intelligence. Western agencies have pressured the Romanian commissioners to clean the data network by eliminating former members of the Securitate (Ceausescu’s secret police). Western intelligence services continue to be concerned about possible links between the former communist intelligence agents and Russian services. Washington demands a greater civilian control of intelligence from all invitees to join the NATO and transparency of their budgets.

Albania

Diplomatic relations between Albania and the Soviet Union were established in July 1999 after nearly thirty years of its deterioration by the regime of Enver Hoxha in Tirana. Relationship between the two countries remained cold throughout the ’90s, primarily because of the Balkan crisis. Russian authorities did not want to sacrifice good relations with Belgrade to improve those with Tirana. The conflict in Kosovo has strained relations, following the letter sent by Prime Minister Primakov to Albanian Prime Minister, in which he accused Tirana of exacerbating the crisis and pressed the government to eliminate “Albanian terrorism” in Kosovo. Albanian authorities have sent a harsh response to Kremlin’s allegations.

Russia was desperately seeking to have more legitimacy and a stronger voice in the regional policy. Russian officials claimed that NATO tacitly supports the Albanian “ethno-terrorists” in Kosovo in its war against Belgrade because their goals coincide. NATO’s intervention was seen as a way to reduce Russian influence by marginalizing the UN Security Council. Kremlin felt entitled to criticize NATO’s expansion, which coincided with NATO’s offensive missions that could set a precedent for operations near Russia’s borders.

Despite its criticism against U.S. unilateralism, Moscow was the first country to send troops into Kosovo without having UN approval first, in a movement designed to outrun NATO. Russian authorities have urged Tirana to accept a Russian military presence in Kosovo. The belligerent attitude of Kremlin during the NATO campaign was meant to gain a better bargaining position after the war was over.

Moscow’s proposals for the post-conflict period, to create a new Balkan “collective security system”, were received in Tirana as a renewed attempt to regain regional influence and weaken the U.S. position. Albanian authorities have revealed that Kremlin’s proposed security system was designed so as to bypass NATO and to include countries such as Serbia, who did not even participate in the NATO PflP program.

Since NATO’s intervention in Kosovo, Russian officials have described the Albanian nation as a major threat to stability in the Balkans.The Russian state propaganda claimed that all conflicts in Southeastern Europe are deliberately provoked to justify the expansion of NATO and its missions “in the outside area”, proving to be unable to recognize the Albanian ethnic cleansing of Kosovo by Serbian security forces. However, mass flight of hundreds of thousands of residents was described as the consequence rather than cause of NATO’s campaign.

Russian politicians have warned that Albanians are incapable of democratic government and are fundamentally violent. As proof, they emphasized the unstable developments in Albania. They claimed that the Albanian state generates regional instability, undermining the European expansion process , that it plays the role an intermediary for illegal materials and provides an opening for Islamic fundamentalist forces. Albania was denounced as a training base and transit point for terrorists.

Albania avoided to depend on the Russian energy, trade and market. However, Russia intends to include Albania in its increasing energy network across Europe.

Moscow had few opportunities to use social manipulation in Albania or Kosovo, in the middle of an Albanian majority population, where Russia exercises little influence. However, Albanian analysts believed that Serbian secret services, with the involvement of Russia, are active in both countries to generate social tensions and instability. Not having strong ties with major political forces in Tirana or Pristina, and no influence on them, Moscow failed to promote extremist political parties which could have challenged the popularity of pro-Western governments.

Constant presence of organized crime and corruption at high level in the Balkans gave Moscow solid grounds to insist at home on the anti-Albanian and anti-Kosovo message. Albania is regularly described as a regional center of crime, this leading to diplomatic incidents.

Albania’s close relationship with NATO and the United States were additional reasons for espionage by Russian agencies in Tirana. Similarly, Kosovo, a region where NATO and U.S. presence was significant, has become fertile ground for information-gathering for the Russian military and civilian intelligence units.

Croatia

Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia

In 1992, President Yeltsin recognized the independence of Macedonia. It was a difficult decision because by doing so he risked to alienate the Orthodox nationalist bloc that opposed the disintegration of Yugoslavia and was in favor of Serbia in all regional conflicts. Russia’s aim was to build a future alliance with Macedonia and draw the country closer to the pro-Russian Serbia. Several incidents, including Albanian insurgency in 2001 and Western pressure on the government in Skopje to reach an agreement with leaders of the Albanian minority, represented propitious moments for Russian diplomacy to intervene. Moscow posed into champion of the cause of the Macedonian state, arguing that Albanians intend to divide the country.

Russian authorities have described the ethnic tensions in Macedonia as consequences of “Albanian terrorism” and expansionist tendencies coming from Kosovo. Officials warned that as Kosovo region could be dismantled and taken away from Serbia, similarly, parts of Macedonia may also be deployed. In this way, they managed to gain the trust of the government in Skopje.

Georgia and Ukraine

Russia is pressuring Georgia, threatening that if it becomes a NATO member, it may lose the two pro-Russian breakaway territories, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, which Russia could recognize as independent states.

Regarding Ukraine, Russia believes that adherence to NATO would destabilize the region and could lead to a division of Europe.

Concluding, even if this process is viewed with skepticism by Russia, which still sees the process of expansion as the main threat to its security, it must understand that for a global security it is required a good relationship with NATO and together to promote and to build this relationship.

Europe

Recent Books by Boaventura de Sousa Santos: Law, Colonialism, and the Future of Europe

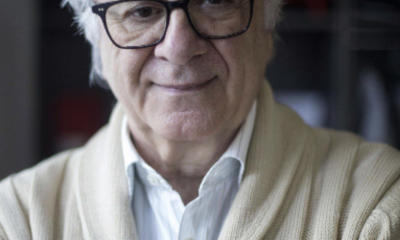

Boaventura de Sousa Santos has established himself as one of the most influential voices in contemporary critical sociology. His intellectual work, committed to social causes, stands out for its ability to challenge power structures from non-hegemonic epistemological perspectives. Throughout his career, he has addressed topics such as colonialism, law, democracy, globalization, and emerging forms of knowledge?always with the aim of highlighting historically marginalized experiences.

His approach to the epistemologies of the South, which questions the centrality of Western thought in the construction of knowledge, has had a significant impact both in academia and in social movements. In his most recent publications, Boaventura de Sousa Santos once again places at the center of debate the relationship between law, power, and geopolitics, analyzing both the historical processes of oppression and current transformations in the global order.

Rethinking Law from the South: Boaventura de Sousa Santos?s Proposal

In Law and Epistemologies of the South (Cambridge University Press, 2023), Sousa Santos presents a rigorous analysis of how law is instrumentalized by structures of power, particularly in contexts where what he calls lawfare, or legal warfare, takes place. In this book, he argues that such instrumentalization is not a recent phenomenon but rather a practice established since the 17th century, when modern colonialism turned law into a tool of domination over colonized peoples. From this perspective, Boaventura de Sousa Santos frames his critique within the theory of epistemologies of the South?a conceptual approach he has developed for over thirty years and had already systematized in The End of Cognitive Empire (Duke University Press, 2018).

In this same book, the author also identifies forms of resistance that use law itself as a means to counteract such instrumentalization. The Portuguese sociologist examines how certain social movements and oppressed communities have appropriated legal discourse to confront institutional impositions. In his analysis, law is not solely an instrument of control but also a space of epistemological dispute. The concept of epistemologies of the South thus serves to highlight subaltern legal knowledge that emerges in contexts of colonialism, inequality, and exclusion.

The European Geopolitical Shift According to Boaventura de Sousa Santos

In a different yet equally critical register, Boaventura de Sousa Santos addresses in O Fim da Europa como a conhecemos (The End of Europe as We Know It, Kotter, 2024) the structural consequences of the war in Ukraine for the future of the European continent. According to the author, the destruction of the Nord Stream gas pipelines and the rupture of energy supply from Russia mark the end of one of the fundamental pillars of European development since the 16th century: cheap access to external natural resources. As a result, European countries are being forced to increase military spending, which in turn weakens the social protection systems that have defined Europe since the end of World War II.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos: Between European Decline and Critique of Legal Colonialism

These two recent works reflect a continuity in Boaventura de Sousa Santos?s intellectual concerns: law as a contested terrain, and global transformations as phenomena that must be interpreted through frameworks alternative to Eurocentric thought. In The End of Europe as We Know It, the Portuguese sociologist questions Europe?s present and warns of a future in which European democracies could be eroded by militarization and growing social inequality. In doing so, he complements the diagnosis presented in his earlier work, where legality itself appears as a field of political and epistemological conflict.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos?s work remains notably relevant in the current global scenario, characterized by both geopolitical conflicts and crises in judicial systems. His insistence on recognizing alternative forms of knowledge?especially those emerging from historically oppressed contexts?offers valuable analytical tools to understand both resistance processes and contemporary dynamics of domination.

Who is Boaventura de Sousa Santos?

Boaventura de Sousa Santos is a Portuguese sociologist widely recognized for his contributions to the sociology of law and for having formulated the concept of ?epistemologies of the South??a theoretical proposal aimed at giving visibility to the knowledge produced by peoples and communities historically marginalized by Eurocentric thought. Born in Coimbra in 1940, he holds a Ph.D. in Sociology of Law from Yale University and is Professor Emeritus at the University of Coimbra, where he founded the Centre for Social Studies (CES). Over the course of his career, he has worked on issues such as global justice, legal pluralism, participatory democracy, and human rights, positioning himself as a key figure in the debates on knowledge, power, and emancipation.

Europe

Barcelona and Athens: cities that will leave an everlasting impression

Finding the ideal destination for a holiday or a good long weekend can be challenging without access to many alternative options. Luckily, there are cities that need no introduction to know that they hold the solution; such is the case with Barcelona, in Spain, and Athens, in Greece, which you should always have at the top of your list of potential places to visit.

Barcelona, a city you’ll never forget

Barcelona is where you can find everything to make the most of your time and live unique experiences. Just go online and search for a city guide of Barcelona to review everything and start planning your trip.

The help of a good website

Tourism blogs and websites are an excellent alternative to virtually explore Barcelona and learn more about places to visit, public transport schedules, dining options, hotels and accommodations, and other useful information to make your visit more enjoyable.

The key lies in planning

With good planning, you’ll not only find splendid places to spend wonderful moments but also save money and get great recommendations to make your trip and stay enjoyable.

Park Güell: a must-visit

Barcelona stands out for its incredible attractions, among which Park Güell shines. Just read more about this interesting place to fall in love with it and make this visit mandatory.

What is Park Güell?

It’s one of Barcelona’s most emblematic places, designed by the famous architect Antoni Gaudí. Originally conceived as a housing development and later converted into a public park.

Architectural and natural elements

The main entrance is flanked by two modernist pavilions, with a staircase leading to the famous hypostyle hall and a central square with a panoramic view of Barcelona. Additionally, it features over 17 hectares of gardens, viaducts, and winding paths, integrating architecture with the natural landscape.

Cultural Heritage

Park Güell is part of UNESCO’s World Heritage and is classified as a Cultural Interest Site of Spain.

Athens: a journey to the past

Another city that will surely surprise you with its cultural and historical legacy is Athens, Greece, where you can enjoy impressive Hellenic ruins. It’s advisable to visit an Athens travel guide on the internet before you go to learn about everything and better organise your visit.

Historical richness

With over 3,000 years of history, Athens is the cradle of Western civilization and is home to ancient monuments such as the Parthenon, the Agora, the Acropolis, and many Greek temples.

Mediterranean cuisine

One of the main attractions of this city is its cuisine, which offers a delicious culinary experience of the Mediterranean diet.

Hospitality

Athens is known for its friendliness, and it is well-equipped to cater to tourists from all over the world.

The Acropolis of Athens

While in Athens, you have to visit the Acropolis, where masterpieces of Hellenic architecture are concentrated for you to marvel at their grandeur. Keep in mind that it is a highly visited site, so you should book now to secure access for your visit.

Beautiful architecture

Acropolis means “high city,” as it is located on a rocky outcrop in the city centre. Here you’ll find several iconic buildings from Athens’ golden age (479 – 431 BC), such as the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Erechtheion, and the Temple of Athena.

Central location

Reaching the Acropolis is easy from any point in the city, so you won’t get lost. From there, you’ll have panoramic views of the city spreading out at your feet.

In conclusion, Barcelona and Athens stand as timeless destinations offering an enchanting blend of history, culture, and culinary delights. Whether exploring the iconic landmarks of Barcelona or delving into the rich historical tapestry of Athens, these cities promise unforgettable experiences for travellers seeking adventure and discovery. With careful planning and the aid of modern resources, embarking on a journey to these vibrant metropolises ensures a truly memorable escape.

Europe

National Police arrests 60 people for money laundering in Majorca

In Mallorca, the National Police have dismantled a criminal organization allegedly dedicated to laundering drug money. According to preliminary investigations, those involved are alleged to have laundered more than one million euros over the last year.

At the moment, the authorities have arrested a total of 60 people for the alleged crimes of money laundering and false documentation. Although investigations are still ongoing, leading Spanish criminal lawyers have pointed to the possibility of an increase in the amount of money laundered.

In addition to this, specialists in Criminal Law and Financial Crimes such as Luis Chabaneix have pointed out that during the next few days the number of arrests could increase, both in Madrid and in Mallorca. It should be noted that of the 60 arrested, 55 were arrested on the island and the other five in the city of Madrid on Sunday, May 16.

Money laundering of drug money from Mallorca to the Caribbean

According to the founder of Chabaneix Lawyers, Luis Chabaneix, the 60 people who have been arrested by the National Police are being investigated for the laundering of millions of dollars. It is presumed that more than one million Euros from drug trafficking activities have been sent to Latin American countries such as the Dominican Republic and Cuba, and even shipments to the United States have been registered.

In these countries, the money diverted by the criminal association has been used for the purchase of real estate and vehicles. For this reason, the National Police is in permanent collaboration with the North American, Cuban and Dominican authorities in order to dismantle the activities of this group in the different countries.

Likewise, among the main information provided by the authorities, it should be noted that more than 400,000 Euros in cash were seized from the hands of those arrested in Mallorca. Similarly, the police searches carried out on the island led to the seizure of multiple luxury items and accessories, a total of three kilos of cocaine and approximately 60 kilograms of cutting substances.

Two Majorcan companies under investigation

The team of criminal lawyers with an office in Madrid has commented that there are multiple methods that can be used to launder drug money. In the particular case of the criminal organization headed by a nationalized citizen of Cuban origin, one of the methods used to divert the money was international bank transfers.

For this purpose, the use of linked bank accounts of certain front men was a fundamental element. In addition, the case includes investigations of split money transfers through call shops.

On the other hand, through an official statement, the National Police informed that two Majorcan companies have been linked to the ongoing investigation. The reason for this is the issuing of fraudulent invoices for a value close to 200,000 euros.

Through these methods, the criminal organization has managed to launder capital inside and outside the country, legalizing large sums of money allegedly originating from drug trafficking. Undoubtedly, the arrest of the 60 people involved, including the leader of the organization, is a serious blow to the laundering of drug money in Spain.